While governments around the world enact and implement laws that give them sweeping powers to fasten their grip over citizens in the light of the coronavirus outbreak, reports of human rights abuses continue to rise. Marginalised and vulnerable sections of the society such as women, children, migrants, minorities and the poor have been most severely affected by the pandemic.‘People in custody’ is one such group susceptible to the fatality of COVID-19. The contagious nature of the disease makes prisons a breeding ground for infections. In the eventuality of even one inmate contracting the virus, the disease will spread like wildfire.

The state of Indian prisons aggravates the severity of an outbreak to several manifolds. According to National Crime Records Bureau data (NCRB) on prisons, the occupancy rate of Indian prisons as on 31st December 2018 was 117.6%. Delhi had an occupancy rate as high as 154.3%. The overcrowding of prisons leaves no scope for social distancing to be practised in the jail complexes. The UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners state, in Rule 63 (3), that the ‘number of prisoners in closed institutions should not be so large that the individualisation of treatment is hindered’. The infection is likely to spread exponentially owing to congested prison cells and shared spaces, as well as the severe lack of general hygiene in jails. This, coupled with the limited access to PPEs, masks, gloves and sanitisers for the staff as well inmates, leave the prisons unmasked to the virulence of the disease. For instance, at the Jaipur Central and District Jail, as many as 338 inmates and the Jail Superintendent were tested positive for COVID. The virus was believed to have spread from a prisoner who was asymptomatic for the 21 days in quarantine. Even though the two Jails have managed to contain the outbreak, Indian Jails are operating on slippery slope.

Courts have not been fully functional during the lockdown imposed to control the outbreak, leading to an increase in the backlog of cases. While access to the judiciary has been a hindrance to the disposal of cases, videoconferencing has been deployed by courts for facilitating resolution of cases. However, only 36.7% of sub-jails and 66% of women’s jails are equipped with facilities for videoconferencing. Central and district jails have relatively better access with about 93% and 81.9% jails respectively, being equipped for the same. This is likely to escalate the number of undertrials to new highs.

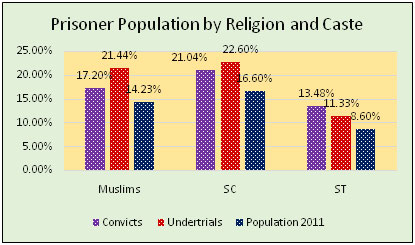

NCRB data pegs the percentage of undertrials at 69.45% as of 31st December 2018. Out of this, 12.1% of the undertrials have been languishing in prisons for 1-2 years now without any recourse. According to World Pre-trial/Remand Imprisonment List (4th edition 2020), published by the Institute for Crime & Justice Policy Research, the world median percentage of population undertrial is 29.5%. In Asia, the median percentage is 26%. The proportion of undertrials in India is already higher than most nations in the world. Moreover, 29% of the undertrial population is illiterate and 39% has received literacy at levels ranging between Class I to Class IX. The lack of education leaves these inmates in the dark about their rights and available procedural remedies. As many as 1,822 undertrials were eligible for release under Section 436A* of CrPc.However, only 60% of them had been released as of 31st December 2018, as cited in NCRB data. The undertrial population is overrepresented by minorities and marginalised groups when compared to their proportion in the country’s population.

Prisons are grossly undermanned, leading to large-scale neglect as well as rising incidence of clashes between inmates and groups. Several episodes of suicides and violence in prison have been reported in the country. Prison Statistics 2018 reported 106 incidences of clashes between groups, leaving about 153 inmates injured. More recently, clashes broke out between the police and inmates at the Dum Dum Central Correctional Home in Kolkata after authorities announced that inmates cannot meet their family members till March 31 in view of the COVID-19 pandemic. Some inmates and police personnel were injured amidst the stone-pelting and firing. In India, there are 9 inmates per jail staff on an average,243 inmates per medical staff and 756 inmates per correctional staff. This clearly indicates that the administrative machinery in the country’s prisons are overburdened.

United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (Nelson Mandela Rules) highlight that prisoners, despite their legal status, should be provided with healthcare standards at par with those available in the community. Moreover, healthcare systems should be aligned to the general public health administration and in a way that ensures continuity of treatment and care, especially in the case of infectious diseases. With many illness prevailing among the prisoners – heart disease, lung infections, tuberculosis and HIV, the COVID-19 outbreak will be merciless on the mortality rates.

In the wake of the increasing spate of infections, the Supreme court issued a directive ordering all states and union territories to set up high-level panels that would consider releasing all convicts who have been jailed for up to seven years on parole to reduce crowding in jails. The court also suggested the setting up of isolation wards, screening, and quarantine of new prisoners, as well as scanning of staff at entry points. The order also recommended ramping up access to medical assistance, improving cleanliness of prison complexes, supplying masks, and limiting personal visits and group activities. States have followed through with this directive, granting paroles or bails in a bid to decongest prisons. Madhya Pradesh (occupancy rate of 147%) has released 5,000 inmates on emergency parole and 3,000 on interim bail.

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights mandates governments to take effective steps for the “prevention, treatment and control of epidemic, endemic, occupational and other diseases”. While countries battle rapidly proliferating number of cases, it is crucial that public health remains accessible to people in a non-discriminatory manner. Jail authorities must prepare a robust plan to eliminate the spread and minimise casualties in case of the disease breaking out in cellular jails. Court cases of undertrials must be reviewed/disposed of promptly on priority basis to reduce the number of inmates. Civil Society and health experts recommend that aged inmates and those suffering from co-morbidities should be considered for release or granted parole swiftly. Disregarding their legal status and protecting prisoners is essential in containing the burden of the disease. Countries all over the world have taken a host of initiatives to prevent prisons from becoming potential hazard zones. Italy has permitted the use of email and Skype for contact between prisoners and their families as well as for educational purposes. Moreover, it has stated its intention to release and place under house arrest prisoners with less than 18 months on their sentence. Iran has temporarily released 85,000 prisoners amidst fear of a viral outbreak in prisons. Bahrain pardoned 901 detainees, released 585 detainees, and granted non-custodial sentences. Protection of human rights of people in custody during a global health crisis speaks volumes about a country’s approach for the defenceless and sets it apart in the global world order.

Note:-

Undertrials who have undergone imprisonment extending up to more than half(1/2) of the sentence for the accused offences cumulatively are eligible for release on personnel bond with or without sureties under this section