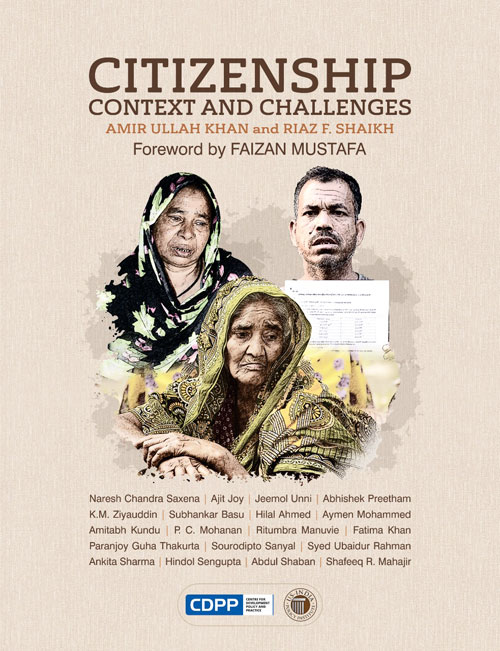

The witticism, “Everybody talks about the weather, but nobody does anything about it,” – commonly misattributed to Mark Twain – perfectly describes the response to the controversial and polarizing Citizenship (Amendment) Act (C.A.A.) 2019, passed by the Government of India on 11 December 2019. True, there was immediate widespread condemnation across the globe, but we felt there was an urgent need to first understand the different facets of citizenship laws, policies, rights, and duties in a comprehensive framework.

We also felt a need to consider the backstory behind the new citizenship laws and the impact of the C.A.A. (along with the equally controversial National Register of Citizens and the National Population Register) on the different aspects of citizenship and on the different sections – particularly the most vulnerable – of the population. While we still cannot do anything about the weather, we embarked on an exploratory journey to chronicle these issues and compiled an edited volume, “Citizenship: Context and Challenges”, featuring some of the finest minds on these topics, including academics, activists, legal luminaries, and public intellectuals. The volume enables dialogue among the different authors with their different viewpoints and ideologies and presents a broad narrative across the spectrum for readers from different backgrounds.

Dr. N.C. Saxena makes a clear distinction between ‘what ought to happen’ and ‘what is likely to happen’ and provides Muslims with a pragmatic blueprint for action in India rather than an idealistic plan in an ideal India. Erudite in content and empathetic in tone, his paper presents the Muslim dilemma of being caught between the vicious cycle of Hindu bias and discrimination followed by protests that lead to further resentment. Citing impeccable academic studies, he describes the perennial history of Muslim problems – discrimination, insecurity, and violence – covertly under earlier regimes and blatantly under the present one. While the community must continue to raise its voice against state-induced atrocities and lack of security in this new illiberal environment, it should also introspect on what it can do independently without inviting the wrath of the majority and promoting communal harmony by reducing Hindu bias against them. He seeks a new breed of leaders – beyond the political and religious – who will kick off a social movement among Muslims towards excellence through self-reliance.

Ajit Joy begins the discussion by taking a historical and legal approach to the current Act, covering the history of citizenship in India from the initial parliamentary discussions and debates on the question of citizenship to the implementation of the Citizenship Act 1955 and all the amendments that followed. Using the case of Assam and its peculiar migrant problems, Joy shows that historical and political circumstances, most notably the partition of India and the political narratives of the threat of the “radical Muslim”, were responsible for these amendments.

He also shows how the judiciary was considerably influenced by a certain nationalistic political narrative, going as far as considering the presence of Bangladeshi migrants in India as nothing short of “aggression”. Joy then uses this historical background to analyze the legal issues surrounding the new Citizenship Act, showing that the Amendment’s classification based on the religious identity of the individual violates Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution. Moreover, the classification based on the religious identity of the individual offends the fundamental principle of secularism, which is enshrined in the basic structure of the Constitution. The court must adjudicate on the matter, leaving the concept of citizenship in a state of flux. Whatever be the decision taken by the Supreme Court, which is in no hurry to do so, this matter will affect Indian citizenship on a fundamental level.

JeemolUnni and Abhishek Preetham follow the trajectory of the concept of citizenship in India from its initial discussion in the Constitution through the various amendments to the Citizenship Act. They go beyond traditional citizenship to consider the concept of ‘economic citizenship’ in academic theory as well as in the Indian context. T.H. Marshall had originally proposed economic citizenship as an extension of citizenship to counterbalance the divisive forces of class inequalities in England, seeing the development of civil, political, and social citizenship as an evolving sequence. Implementing this in an Indian context will be challenging as society here is beset by linguistic, ethnic, and religious fault lines.

Even in the presence of these rights, the State does not follow its obligation to guarantee political and economic participation of all its citizens. A vast segment of the Indian population misses out on socioeconomic citizenship through exclusionary legislative and bureaucratic activity at the lower levels of Government followed by remedial inaction at the higher levels of Government. The authors conclude that C.A.A.-2019 would have a significant negative impact on the idea – as well as the implementation – of economic citizenship, would lead to discriminatory citizenship, and draw global criticism.

K.M. Ziyauddin and SubhankarBasu give a historical perspective on the question of Muslims. While the concept of a nation-state is invariably linked to citizenship, the Indian case is particularly complex and politically motivated. The authors put various events – from Independence and the partition of India to the Citizenship Amendment Act – into perspective to understand the question of Muslims given larger perceptions about them. The paper captures the Constitutional and statutory provisions of citizenship in light of sociopolitical ideology amid ongoing debates, discourses, and popular demand for a truly secular state strong enough to deter divisive politics for the unity and integrity of the nation and keeping India’s heterogeneity and diversity as a nation-state.

Hilal Ahmed views the Citizenship Amendment Act as an essentially political phenomenon and seeks to understand its emergence, evolution, and responses to it by opposing – mainly Muslim – protests. Ahmed shows that traditional and popular dichotomy – between hindutva-nationalism and liberal-constitutionalism – that is often deployed to analyze the Act is very misleading. He shows that the whole concept of Hindu nationalism has changed considerably since 1950, when D.V. Savarkar criticized the Constitution but Narendra Modi today considers it a “Holy Book”. The traditional stereotype of anti-Constitutional hindutva is outdated, replaced by an emerging politics of hindutva-constitutionalism. This new ideological hegemony appropriates the Constitution for creating a new Hindu majoritarian common sense. Not understanding this new politic, the Muslim response has largely failed as they could not come up with an appropriate critique of the new hegemony , arguing that the Indian Constitution is a self-explanatory political text with a protected and unquestionable secular character. This over-reliance on the Constitution as a source of politics has proven to be very problematic as other major political parties seem to have accepted hindutva as a dominant political narrative.

Aymen Mohammed explores the intersections of citizenship and federalism and goes beyond State compliance and cooperative federalism to look at the nature of the cooperation or the lack thereof. India’s citizenship framework grants the Union exclusive power to deal with matters concerning citizenship with the power of implementing key citizenship laws resting with the states. Unless federalism is underpinned by the Constitutional value of fraternity, it is unlikely for the Union and states to cooperate in a Constitutional manner. Cooperative institutional arrangements that are respectful to the principle of equal and inclusive citizenship are possible but they require the Union to view the interaction of federalism and citizenship not as isolated issues pertaining to routine administration but as a question of Constitutional rights.

Amitabh Kundu and P.C. Mohanan take a broader perspective of citizenship and go beyond simply the right to live in a country, move freely within it, have voting rights, and equal access to the law. They insist on access to employment anywhere in the country, no discrimination in any civil matter, and access to all welfare programs of the State. They dissect the anatomy of the population register and identify errors in coverage and content. They argue that the burden of proving citizenship will be the greatest on the weakest sections and citizenship policies will impact migrants the most. In addition to this burden, migrants will also face discrimination as several states have – or are considering – legal job reservations for locals which go against Article 16 of the Constitution that promises equal employment opportunities through the Inter-State Migrant Workmen Act (1979).

RitumbraManuvie explores citizenship and its rights from the lens of environmental disasters and the resultant displacement of citizens, particularly in Assam, an ecologically sensitive state. Communities that live along the geographical margins of climate vulnerability are also occupying the political periphery of citizenship, she argues. Despite the 2016 U.N. Declaration for Refugees and Migrants and the Global Compact on Migrants – both of which include commitments to address the impact of climate change on forced movement – there is a complete disconnect between these ideals and ground realities.

Her literature review of climate change migration finds that there is undue emphasis on the lack of a coherent international policy and an assumption that national and provincial governments show sympathy and economic support for such migrants. Yet, state officials in Assam admit that policy outcomes are either insufficient or absent and are beset by problems like corruption, bureaucracy, inadequacy, and identification issues. Suspicions around ‘illegal Bangladeshi immigrants’ remains enduringly etched in not just social but also in the government’s interaction with its people, a colonial era anti-migrant sentiment that has only gained strength in independent India.

Fatima Khan offers her experiences as a traveling journalist who investigated the communal violence that occurred in the aftermath of the C.A.A. protests in Delhi and Uttar Pradesh from December 2019 to February 2020. She shares a gripping tale of violence and displacement experienced by Muslims in the aftermath of the anti-C.A.A. protests. People were brutally murdered and houses were set on fire. These killings and looting, Fatima contends, occurred with “State-complicity”, by which she means that the state passively watched as it was unfolding. In addition to reporting violence occurring at the time, Khan also shows what was its long-term impact on communal harmony between Muslims and Hindus. People who lived for years in harmony were now becoming alarmingly suspicious about their neighbors. She ends by emphasizing the struggles endured by protestors at Shaheen Bagh, mainly “Dadhis” who valiantly stood in the biting cold demanding their voices be heard. They did not give up in despair and neither should anyone who wishes to stand against injustice.

Paranjoy Guha Thakurta and Sourodipto Sanyal investigate the role of the Indian mass media – which became increasingly colored by majoritarian narratives – especially since mid-2014 in demonizing minorities. Mass media and telecommunication systems are extremely important in a democracy, so much so that some have dubbed them as the “fourth estate” of democratic rule. By virtue of the incredible power vested in them, it becomes vital that they are not used as propaganda weapons of majoritarian political narratives. Unfortunately, this is exactly the case, Thakurta and Sanyal argue. Even social media platforms such as Facebook and WhatsApp have bowed to the B.J.P. and allowed themselves to be rigorously used to disseminate hatred against minorities.

Thakurta and Sanyal also show how mainstream media spread misinformation about the C.A.A. protests, going as far as publicly displaying their political biases by demonizing the anti-C.A.A. protests and praising the law’s supporters. Several reports by respected journalists illustrate that a majority of the print and televisual media has spent considerable time and energy trying to label relatively peaceful anti-C.A.A. protests as nothing short of a violent conspiracy and a threat to Indian society, similar to Jammu and Kashmir where the government issued a complete communications blockade, denying residents any access to the internet or telecom services. Even the relatively secular farmer protests have received unfair treatment at the hands of the Indian media.

Ubaidur Rahman turns the discussion towards history and tries to show major contributions made by the Muslim Ulema (scholars) during the Independence struggle. He first sketches a brief biography of the famous Maulana Husain Ahmed Madani, one of the most respected and learned Ulema of the Indian sub-continent. Maulana Madni, as he was known, was one of the most vocal Muslim voices against the British Raj. He claimed that Muslims had a spiritual – in addition to a purely physical – connection to India as many Prophets were sent here by Allah. Not only was Maulana Madni a champion of independence, but also a major figure calling for Hindu-Muslim unity, as Rahman shows by directly quoting many of the Maulana’s speeches. Another towering figure was Maulana Ahmad Ullah Shah who played a pivotal role in the Mutiny of 1857.

The Maulana was the only person who dared to defeat the dangerous Sir Collin Campbell twice. The struggles of the Muslim Ulema were not just limited to extraordinary performances by individuals though. The Ulema collectively started an organization called “Jamiat Ulama” whose main goal was to get complete independence from British rule. The Jamiat worked alongside the Indian National Congress in their struggle for independence against the British and a partition of India. Surely, Rahman reasons, Muslims cannot have their citizenship questioned when their forefathers gave every possible sacrifice for the nation.

Hindol Sengupta and Ankita Sharma go beyond the question of what ‘makes’ a citizen to what one ‘does’ as a citizen. If the fundamental idea in digital citizenship is the adoption and use of digital technologies powered by the internet in fulfilling acts of citizenship, digital citizens are those “who use the internet regularly and effectively”. The e-interaction between the State and citizens using digital tools can be divided into three models of participation’: managerial, consultative, and participatory, where the managerial model can be defined as a unilinear framework highlighting efficient delivery of Government/state information to citizens and other groups of users. The authors elucidate the contemporary managerial nature of the digital interaction between the Indian state and its citizens through the working of two key technological interfaces: (i) Direct Benefit Transfers through the JAM (Jan- Dhan Yojana, Aadhaar and mobile phone) trinity and the use of the (ii) AarogyaSetu mobile application.

Abdul Shaban provides an evenhanded examination of the future of Muslim citizenship in India. While it is an undeniable fact that the quality of Muslim citizenship is poor in comparison to other religious groups in the country, he provides a scathing analysis of both the internal and external factors responsible for this. On the one hand, there have been attempts to progressively stigmatize the community and its culture and change the relation of state and other social institutions against Muslims while on the other, conservative elements refuse to reform and adopt a more progressive, development-oriented approach. Ordinary Muslims can get “fuller” citizenship only if both Hindus and Muslims provide reconciliatory leadership, bridge a widening communal divide, and give a healing touch to historical wounds for building a progressive society.

Shafiq Mahajir aims to refute some of the claims regarding the mass persecutions of non-Muslims in Muslim-dominated countries. Mahajir argues that these claims, based on faulty population statistics, confirm the baseless specter of Muslims over- running the country. These – instead of pure facts – are commonly used as a justification for increasing hostility and bigotry towards Muslims. Mahajir also gives a historical account of the Citizenship Amendment Act. He shows how an ostensibly “unbiased” judiciary gave in to a political and nationalist narrative, disregarding justice and equity for supposed “national interests”. He highlights the case of Kumar Rani – an Indian who emigrated to Pakistan and back – who had all her property confiscated by the Indian Government after receiving a biased judgment from the judiciary. This judgment unfortunately set a wrongful precedent against Muslims that is continued to this day. Mahajir concludes by saying that the decision taken by the Supreme court on the legality of the Citizenship Act (2019) indicates what direction the judiciary in this country is heading in; whether it is moving towards enforcing justice and rights or disregarding them entirely. In either case, the matter is over to the citizens.

This volume is only a beginning, made to understand the rather sophisticated and seriously misunderstood concept of citizenship. There has been little academic or policy debate on the issue that was monopolized almost completely by political narratives. In this volume, we have attempted to get scholars from various disciplines to look at the various aspects of the citizenship dilemma and provide robust academic rigor to the issue that was discussed at length throughout 2019 and is bound to rear its head again after fears around COVID-19 recede and a new election cycle begins. This ongoing effort by USIPI and CDPP will hopefully go some distance in clarifying a few concerns raised by those who worry about citizenship rights.

Themes explored

The Muslim Dilemma in Independent India

Naresh Chandra Saxena

Citizenship in India: A Legal Framework

Ajit Joy

The Idea of Economic Citizenship and the Citizenship Act 63

Abhishek Preetham and JeemolUnni

Citizenship Debates since the Independence of India: The Question of Muslims

K.M. Ziyauddin and SubhankarBasu

Making Sense of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) 2019: Process, Politics and Protests

Hilal Ahmed

(Non-) Cooperative Federalism and Fraternal Citizenship in India

Aymen Mohammed

Citizenship: Issues with Special Reference to Migration

Amitabh Kundu and P. C. Mohanan

Disasters, Displacement and Citizenship Rights

Dr. RitumbraManuvie

Losing the ‘Right to have Rights’: How Violence was used as a tool to Render Muslims Lesser Citizens after Anti-CAA Protests

Fatima Khan

Indian Media’s Failure to Safeguard Citizens’ Rights

Paranjoy Guha Thakurta and Sourodipto Sanyal

The Citizenship Question and Muslim Ulema’s

Syed Ubaidur Rahman

Digital Citizenship in India: Analyzing the ‘Managerial’ Nature of the State-Citizen Digital Interaction

Ankita Sharma and Hindol Sengupta

Future of Muslim Citizenship in India

Abdul Shaban

Examining Legal and Constitutional Aspects; its over to you, Citizens

Shafeeq Rehman Mahajir