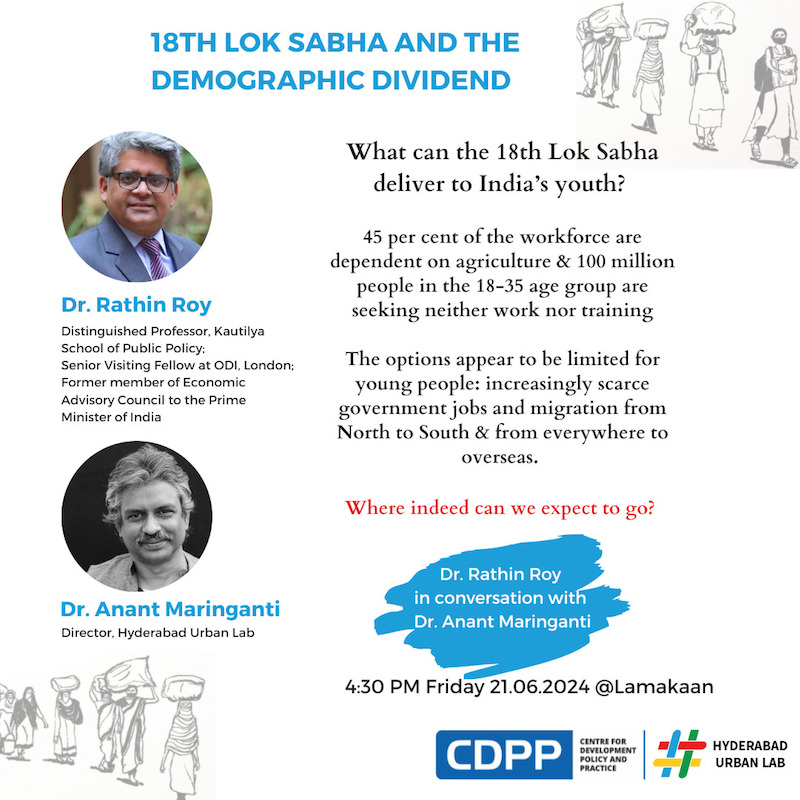

Date and Time: 21st June 2024, Friday 4:30 PM

Location: Lamakaan, Banjara Hills, Hyderabad

Organisers: CDPP and Hyderabad Urban Research Lab

Purpose: What can the 18th Lok Sabha deliver to India’s youth? 45% of the workforce are dependent on agriculture and 100 million people in the age group 18-35 are neither seeking work or training. The options appear to be limited for young people; with increasingly scarce government jobs and migration from North to South & from everywhere to overseas. Where indeed can we expect to go?

Participants

Speaker: Dr. Rathin Roy (Distinguished Professor, Kautilya School of Public Policy, Senior Visiting Fellow at ODI, London: Former member of Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister of India.)

Moderator: Dr. Anant Maringanti (Director, Hyderabad Urban Lab)

Agenda

To discuss the challenges and opportunities for India's youth. The discussion will explore what the 18th Lok Sabha can do to address these issues and improve the lives of young Indians.

Key Points: Dr. Rathin Roy

Dr. Roy paints a concerning picture of India's economic trajectory. He argues that the gains from economic growth are concentrated among a select few. Profits for corporations have soared, while wages, interest, and rents haven't kept pace. This benefits a wealthy class of about 70 million people, widening the gap between rich and poor.

To maintain stability, the government has become a "compensatory state," heavily reliant on handouts to a vast population of around 800 million. This approach, adopted by all major political parties, prioritises short-term solutions over genuine development efforts. Voters are left with limited choices, as politicians focus on immediate compensation rather than long-term economic progress.

The recent elections offered little hope for change. While apprenticeship programs in some states provided temporary relief, they didn't address the larger issue. Voters are looking beyond immediate measures and want a more inclusive long-term vision for the country.

Dr. Roy challenges the traditional definition of development focused solely on overcoming poverty. He points out that reaching middle-income status doesn't guarantee true progress, citing examples like Japan and South Korea. These countries, despite their relative wealth, still face challenges like poverty, health issues, and educational disparities. India needs solutions beyond just achieving a certain income level.

The role of young people is critical in Dr. Roy's vision for change. The failure of the NEET exam, for instance, could be a turning point. It highlights the need for a more equitable education system that doesn't exploit underprivileged youth. Increased youth participation in politics would lead to better public discourse and more productive policies.

Finally, Dr. Roy raises concerns about India's unique socio-economic landscape. There are vast economic disparities between states, with some like Tamil Nadu reaching income levels comparable to Indonesia, while others like Bihar lag behind Nepal. The government uses fiscal transfers to bridge this gap, but this approach creates a north-south political divide. This situation, where the majority of the population lives in poorer regions, is similar to former Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, and could lead to instability if left unaddressed.

In conclusion, Dr. Roy presents two contrasting narratives of India. The stock market thrives on a slow-growing, exclusive economy managed by an incompetent government. The reality for most people is an economy that doesn't create shared prosperity. While the recent election didn't offer solutions, there's still hope for change. Factors like growing discontent among youth, the north-south divide, and economic challenges could force a shift towards a more inclusive and sustainable economic model, led by young, conscious politicians.

Question and Answer Session

Q: How does speculation in the economy affect structural transformation, particularly in the context of employment and economic growth?

A: Speculation in the economy can hinder structural transformation by prioritising short-term gains over long-term investments in areas like infrastructure and education. This can lead to a gig economy with unstable jobs and limited growth potential.

Q: Are you critical of the Aam Aadmi Party's approach?

A: My position is not necessarily a critique of Aam Aadmi specifically, but rather a focus on achieving a sustainable solution to poverty.

Q: Can you elaborate on your critique of the current economic system in India?

A: The current system seems to rely on a combination of speculation and handouts. While handouts like subsidised food are necessary for immediate relief, they don't address the root causes of poverty. Ideally, the goal should be to create an economic system where people can earn enough to afford necessities like food and education. This requires structural changes that promote job creation and upward mobility. Charity has a role to play in emergencies, but a healthy economy should empower people to meet their own needs through employment.

Q: What are your solutions to the problems you mentioned, like the overreliance on handouts? Is universal basic income (UBI) a potential answer?

A: We need to move away from a system based solely on handouts and create an economy that fosters job creation and upward mobility. This could involve investments in education, infrastructure, and sectors with high growth potential. Universal basic income (UBI) could be a potential solution, but it needs careful consideration. It could provide a safety net while people find jobs, but the specifics of implementation and funding need to be addressed.

Q: How can the stock market play a role in achieving prosperity?

A: A healthy stock market can play a role by attracting investments and fueling economic growth. However, it shouldn't come at the expense of long-term structural changes.

Q: What kind of political movement is needed to achieve these goals?

A: The answer lies in creating an agenda focused on prosperity, not handouts. This might require a new political movement that isn't beholden to dynasties. Unfortunately, the current political landscape doesn’t look too good. There's a lack of fresh perspectives and a need for more "street" politicians who understand the struggles of ordinary people. However, this change is difficult to achieve.

Q: Is it because of the worship of the BJP party and their loyalty to the leader that people are not able to earn for themselves?

A: BJP is not the only party that delivers, rather it is the only party that uses the party system to deliver. Other parties use IAS, contractors, etc to deliver. Only DMK and BJP use the party to deliver, creating a different connection with the people. Only recently have Modi and Shah started to use the civil services to deliver, marking a slight change.

Q: Recent scandals involving student exams and the UGC exam raise concerns about the fairness and effectiveness of these systems. If we discard these traditional exams, what alternatives could be used to assess student capabilities and potential?

A: Roy quotes the RSS here, saying “Do what you want to do and don't worry about the result.” What the exam is offering you is a probabilistic chance of joining the system that will soon exploit you. You will not be able to subvert that system from behind due to the inherent logic that it has. You can quit halfway, but you cannot change it. The question of alternatives to traditional exams is complex. There's no single perfect solution, and the best approach might involve a combination of methods.

Q: Do you look at reservations as a non-financial freebie? If yes, why? If not, why?

A: Reservations are palliatives that have not solved the substantial problem in this country. Despite reservations, why are there so few backward classes people in the real-world workplaces? Performatively, our president is a Dalit, but what are reservations doing? Reservations were an attempt to solve a problem, an attempt that failed. You cannot say that they are unfair to people who believe they are denied opportunities, rather, choose a solution that is not reservation. Can you, do it?

Q: When people pay taxes, what are their legitimate expectations? Is it reasonable for taxpayers to question how their tax money is spent?

A: People who pay taxes have a right to expect that their money is used effectively and efficiently. This includes funding essential public services like infrastructure, healthcare, and education. The concern raised here is that the government might be over-reliant on social programs to "compensate" for a lack of opportunity in areas like education and job creation. Ideally, a healthy tax system should not just provide a safety net but also invest in creating a society where fewer people require that safety net.

Q: India's economic growth in the past decade has been underwhelming, and resource utilization seems inefficient. What are the long-term consequences of this trend? How serious is the situation?

A: India is a weak state. This is for two reasons. Firstly, it is a low ambition state, and the state has lost confidence that it can actually do the things people expect it to. The philosophy should be: if you can do it, you can afford it. Money cannot be used as an excuse. The real question is: can you, do it? And this confidence has dwindled in the government. In fact, the government doesn’t want to know the answer to important questions because they aren’t sure if they can fix them. Second, the state is caught in a childish loop of inaction, where they say they will do something, but it is so drawn out that nothing happens. The state has shrunk. This is because they don’t have confidence. When doing labharthi, you’re taking money from someone and giving it to someone else. What problems does this solve? It’s not hard work, so it happens easily.

Q: For the longest time, people who were in the media and the opposition, were thinking that the congress is playing caste politics and that they can challenge the narrative. Now, what do we do? Will regional parties ever be able to get together and put themselves out as an alternative? Or can they not, as the only thing they know how to do is be in a compensatory state?

A: Focusing solely on the state is insufficient. India's problems stem from a "low fraternity" society, lacking social cohesion. Political parties are stuck in handout politics, neglecting social movements that could foster a sense of community. Education is treated as a technical problem, not a way to cultivate well-rounded individuals. The solution lies in reviving social movements and public discourse. Historical examples like government colleges built through social initiatives highlight the need for a shift from state-centric solutions to fostering a more engaged and collaborative society. This societal change, not just political alternatives, is what India truly needs. “From fraternity comes prosperity.”

Transcription

The speaker argues that the economic story of India has failed for the vast majority of the population. He identified four ways to make money: wages, interest, rent, and profit. In India, while profits have boomed for a small number of companies, wages, interest, and rents have either stagnated or declined. This economic trend benefits a select few, primarily large corporations and shareholders, as evidenced by the booming stock market. India has a large and wealthy middle class. He argues that this economic structure perpetuates inequality, benefiting only about 70 million wealthy Indians - akin to entire markets in countries like Germany or the UK. This situation relates to historical contexts such as the Russian Revolution, highlighting the challenge of managing discontent among the majority of the population who do not share in these economic gains. He argues that to keep this group happy and the economy stable, the government must provide handouts to the remaining 1 billion people in India. This keeps the people from getting too unhappy and demanding more, which could lead to social unrest.

Speaking about the Indian government's approach over the past decade, Roy highlights a shift towards what he terms as a ‘compensatory state’. There is a stark disparity where profits have surged while wages stagnate, leading to the emergence of a vast group dependent on food subsidies and other forms of government aid, amounting to about 800 million people. The people who rely on these compensatory programs are termed ‘labharthi’. This shift can be traced back to 1991, but it accelerated significantly since 2014. He argues that all major political parties agree on this approach, making it difficult to have an ideological debate or propose alternative solutions. This compensatory role has become the primary function of both state and central governments, overshadowing efforts towards genuine development transformation.

Dr. Roy was disappointed with the political landscape, criticising all major parties, including the BJP, for creating a system that benefits the wealthy while offering minimal economic opportunity to the majority. Taking Maharashtra as an example, he spoke about the growing discontent among younger generations, who feel let down by the lack of employment opportunities and the government's focus on compensation rather than economic progress. Without a progressive approach focused on genuine economic growth and opportunity for all, India's future risks being dominated by short-term compensatory measures that fail to address long-term structural issues.

He then analyses the election outcomes through the lens of economic policy. There were two aspects discussed here. First, Dr. Roy mentions that the apprenticeship scheme in Maharashtra was a good initiative for offering youth tangible opportunities. However, he also brings up the fact that such programs have not resonated similarly in other states like Gujarat, Rajasthan, or Madhya Pradesh. This regional disparity shows that economic prosperity does not translate into unified political support. This means that people are looking beyond immediate measures and are looking for more inclusive, long-term solutions. The second aspect is the involvement of political parties. Roy speaks about how the BJP is one of the very few parties in India to deliver on their projects, while other parties like the Congress rely on state governments and civil services for implementing projects, creating a disconnect from the people. This creates a political vacuum, where in the absence of a party offering a vision for shared prosperity, voters are left with the option of parties that provide compensation.

Dr. Roy challenges the common narrative of development that portrays overcoming struggles as the sole path to a happy ending for nations. There needs to be a more nuanced view. Simply reaching a certain income level doesn't guarantee true progress. Many developing countries haven't achieved lasting improvements despite reaching a middle-income status. These include countries like Japan, South Korea, and Western Europe. They have achieved prosperity but remain trapped in "$10,000 per capita basket cases." These countries face persistent poverty, health issues, and educational challenges despite their relative wealth compared to India. He comes back to the importance of long-term solutions. The recent election, however, did nothing to address the underlying issues hindering India's potential. Despite this, he believes that there's still a chance for India to improve. There is a possibility of change through better policies and a more productive public discourse.

There is a lack of clear direction in India’s policy. Young people need to be more involved in politics and challenge the status quo. This is where Roy brings up the failure of NEET. The scandal led to a huge number of people challenging the NTA. A large portion of India's intelligent young people, especially those from underprivileged backgrounds, are being exploited by the current system. The system not only determines who enters government service, but also influences how young people perceive success and participate in the "Indian dream.” In a future where the legitimacy of these exams and the broader education system could be questioned, young people would engage with the system, creating better discourse in politics. In that sense, Roy argues that he needed NEET to fail in order to pave the way to a better future for the country.

The final point was a troubling observation about India's unique socio-economic landscape compared to other countries. States like Tamil Nadu have per capita incomes comparable to Indonesia, while others like Bihar are below Nepal's level. This disparity has been a consistent feature for several decades, shaped by complex historical and economic factors. The government tries to overcome these disparities through fiscal transfers from richer states to poorer states. However, this also creates a stronger political divide between the North and the South. The upcoming delimitation in 2026 could give more political power to northern states. This situation that India is in is unique. In most countries, richer areas tend to have a larger population. India's situation, where the majority lives in poorer regions, is similar to former Yugoslavia and the former Soviet Union, which eventually collapsed. This growing economic and political divide could lead to major political instability in India unless addressed through comprehensive reforms.

Dr. Roy concludes by saying that there are two contrasting narratives of India depending on one's perspective: the stock market story versus the broader economic reality. The stock market thrives on an exclusive, slow-growing economy managed by an incompetent government. This keeps the stock market successful and benefits a select few. The other story, the one for most people, is of an economy that doesn't create prosperity. This disappointment wasn't reflected in the recent election, and politicians are focused on handout schemes rather than development. The hope for change lies in young, conscious politicians. The factors that might drive this change could be the competitive exams, the growing north-south divide, and difficult economic choices. “Will all these things lead to a happy ending? Probably not, but it opens up the possibility.”